Update: Mercury Racing just said the price for the QC4v crate engine will around $68,000 without wiring harness, ECU and turbos. Basically it will be as shown below on the left, but all engines are custom-built so numerous options are available to customers.

A 9.0-liter all-aluminum DOHC, twin-turbocharged V8 engine making more than 1,600 horsepower should draw attention in the automotive community. But this engine was originally developed by Mercury Racing, a division of Mercury Marine, to power massive off-shore speedboats. To be sure, it is a little on the stocky side — measuring almost 33 inches from cam cover to cam cover — and it tips the scales at 660 pounds stripped naked. With turbos and pumps, this beast weighs over 900 pounds.

“But we thought all along about an automotive platform because of the torque curve,” says Mercury’s Rick Mackie.

To demonstrate the engine’s viability as a crate motor and also its compatibility with four wheels, Mercury Racing slightly modified its QC4v engine and stuffed it into what originally was an Ultima kit car. It was a snug fit, but the engine sits nicely in the 2-seater just in front of a Ford GT transaxle.

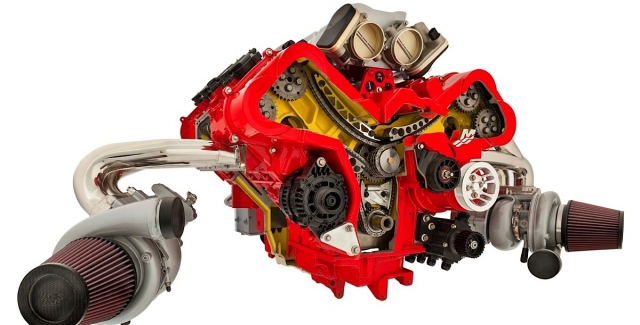

Views of the QC4v as a potential crate engine on the left, and how it's delivered with a stern drive to the marine market.

“We do have a prototype intake to get the overall height down,” adds Mackie. “And we had to adapt the ECU program to give the engine more drivability.”

Getting the engine to work in a such a small environment certainly offers promise to the prospective car customizer who wants a truly exotic machine. Can you envision this powerplant in a ’70 Chevelle or ’57 F-100 as well as a street rod? How about a monster truck or truck puller, if you want to go racing?

The QC4v will be available from a basic long-block to a turn-key offering. Every engine is basically custom built at Mercury Racing, giving customers plenty of choices in configuration as well as colors.

“It’s capable of 1,350 horsepower on pump fuel,” adds Mackie, adding that the 1650 marine version makes 1,650 horsepower on 112-octane race fuel.

Each engine is custom built, so Mercury Racing can offer different colors and finishes.

The alloy block featues NiCom-coated cylinder bores measuring 4.57 inches, and the crank stroke extends 4.21 inches for a total displacement of 552ci. The crankcase is a dry-sump design with oil scavenged from three locations. Oil return from the top end is mostly through huge passages leading down through each timing-chain cover as well as smaller ports on each head that drain lubricant back through the block to the sump.

The dry-sump system and intake manifold.

The dual-overhead-cam cylinder heads feature finger followers to activate the 32 valves. The cams are driven by three chains: one from the crank to a cam-drive sprocket, and then two chains drive the twin cams in each bank. Inlet ports on the cylinder head are actually a single large oval that feeds both intake valves per cylinder.

Key to the power output — at least in full-race marine applications — is a unique twin-turbo arrangement that uses cast exhaust manifolds that are as stunning aesthetically as they are functional.

“We opted to communicate the pulse tuning of the exhaust system through subtle relief in the casting surfaces, indicating the pairing of ports and the side-to-side differences,” explains former Mercury Racing president Fred Kiekhaefer, son of Carl Keikhaefer, the founder of Mercury Marine who also won two NASCAR championships as a car owner. “This also helped function, maintaining high scrubbing speed of the manifold cooling water.”

Engine cutaway shows the valvetrain and manifold design.

For the prototype car application, Mercury fabbed up tubular headers to position the turbos down low and help facilitate routing for the intercooler plumbing. But other highly stylized features of the marine engine carried over, such as the fuel rails.

The turbos on the prototype car retained their marine-style water-cooling feature, however, crate-engine customers could design their own custom setup using aftermarket turbos. Customers will also have a choice of using the Mercury ECU with customizable software to control fuel delivery, spark timing — which is handled with individual coils per cylinder — and turbo activity, or any number of high-end aftermarket controllers can be adapted.

Mercury didn’t release full dyno numbers with the crate engine’s introduction at SEMA. Mercury promotional materials are also rather vague, noting that the 1,650 version is rated at 1,650 horsepower at the crank. A blog by Keikhaefer revealed the 1,350 version of the engine — which has smaller turbos — demonstrated 1,370 lb-ft of torque from 2,500 up to 5,250 rpm. So, a properly prepared QC4v certainly has the potential for 1,500+ lb-ft of torque through the same power range without giving up too much in street manners.

No doubt a competent engine builder can get those types of numbers from a tall-deck big-block Chevy, but it may require a little more displacement and lumpy camshaft. Exactly how streetable the Mercury Marine QC4v crate engine really is remains to be seen. Even the prototype vehicle was needing a few more adjustments and extra tuning before it would be deemed ready for road tests. But there’s little hesitation in acknowledging that the QC4v offers exciting potential as a unique powerplant for high-end performance and show vehicles.