In an age when some drivers know more about the engine specs of their private jet than their racecar, looking back on Dave Marcis’ career is a refreshing diversion from the pop-culture celebrity worship in today’s motorsports. Marcis was one of the last truly independent NASCAR Cup drivers who spun his own wrenches, drove his own tow vehicle and put every penny he earned from the track back into his garage.

As an engine builder, Marcis didn’t uncover any revolutionary power formulas, but he manifested an honorable work ethic based on the oft-forgotten auto racing mantra: Build it. Drive it. Fix it. Live with it!

When was the last time you saw a NASCAR driver with hands that dirty? Marcis continues to work on cars when he’s not helping wife Helen run a restaurant in Wisconsin.

Aside from a few NHRA Pro Stock racers running their own engines, there isn’t a Tier 1 motorsport where the “engine builder/driver” job title is clearly evident. With development costs skyrocketing, there’s little chance for an independent engine builder who’s also a hot shoe to achieve success in an upper-level racing division.

“The day of the independent driver in NASCAR’s top ranks is now a thing of the past, but Dave’s approach to racing can still be used as a very valuable learning tool for drivers in other series trying to make a name for themselves on a shoestring budget,” praises leading team owner Richard Childress, who traded used engine parts to Marcis in exchange for test driving duties on Dale Earnhardt’s car. “Back in the 70s, Dave was always really competitive for what he had to race with. He was the lead independent driver, and all the rest of us tried to learn from him to get better and get by. He was just one of those guys who did more with less than anybody out there.”

Marcis’ do-it-yourself convictions started early in his father’s Wisconsin repair shop. He raced short tracks with a Ford flathead, but his dad wasn’t always available to help. “I pretty much learned everything on my own with trial and error,” he remembers.

Daytona or Bust – and he did!

By 1968 he was ready to challenge the high banks of Daytona with a ’66 Chevy sponsored by hometown Chevrolet dealer Larry Wehrs; that is, if he could get to the Florida coast. Near Bowling Green, Kentucky, the engine in his tow truck seized. With no money for repairs, he dropped the oil pan in a rest area, revealing a burned rod bearing and busted connecting rod.

“I got a torch up in there to cut the sides off the wrist pin,” says Marcis. “I just left the piston jammed up in cylinder.”

Dave Marcis: By the Numbers

- 881 NASCAR Cup race starts

- 14 poles

- 5 victories: Martinsville (‘75), Richmond (‘76, ‘82), Atlanta (‘76) and Taladega (‘76)

- 93 top-5 finishes

- 221 top-10 finishes

- 33 starts in Daytona 500, more than any other driver

- 60 years old when he started his final Daytona 500

- 8 times finished in top-10 season points

- 2nd in points in 1975, losing to Richard Petty

- 2001 – Won Buddy Shuman Award

Marcis wrapped the exposed rod journal with duct tape to cover the oil holes, and he bolted what was left of the rod and cap over the tape to help maintain oil pressure. He buttoned up the pan and reused the same oil.

“I did dump an entire case of STP in the engine,” Marcis, who finished the trip on seven cylinders and never getting above 30 mph. “It vibrated so hard you couldn’t hardly hold your hand on the steering wheel. Couldn’t read any of the gauges, either.”

When Marcis reached Daytona, Smokey Yunick helped out in two ways: He let Marcis swap a new short block into his truck at his shop, and he offered valvetrain advice.

“I was having problems with the pushrods in my 427,” says Marcis. “He gave me a set of pushrods. He told me to call Bill Howell at General Motors, and he could have more sent to my Chevy dealer in Wisconsin. So I called Bill, and he said he had never heard of that part number.”

That first set of pushrods lasted quite a few races before Smokey donated another set. Back then, engines had to survive multiple race weekends.

“The Hemis could go three races. The small blocks could run at least two before pulling them apart to replace the rings and bearings,” says Marcis, whose driving trademark was wearing Dexter wingtip shoes to resist the floorpan heat. “Some of the cranks and rods probably lasted five races.”

“One of the best stories about Dave that I can remember is when Dale Earnhardt came into the Cup series as a rookie in 1979,” adds Childress. “We were at Martinsville and Earnhardt was messing with Dave on the track. Dave had had enough and he spun Earnhardt on the back stretch. He let Earnhardt know right away that he wasn’t going to take anything off of him.”

Understanding flow

Marcis made due with three or four blocks during a full season of racing, usually performing about 10 rebuilds. A standard Chevy 350 block was Marcis’ starting point. Leo Jackson would install 4-bolt mains and rework the oiling passages. Dewey Livengood handled most of the cylinder head work.

“Dave was one of the first owners to get a flow bench,” praises Livengood, who finished his career working on Richard Childress’ engine development team. “We learned a lot with that bench. Before, you did it the way you thought was right, but we had no way of testing except on the track.”

“Dewey always worked the flowbench, making different tapers in the intake,” says Marcis. “I still got manifolds in the shop that he cut up and welded, then sandblasted so you couldn’t tell they’d been apart.

Marcis was a close friend to seven-time Cup champion Dale Earnhardt and helped set up Earnhardt’s car before his Daytona victory in 1998. On the right, Marcis with longtime engine-building buddy Dewey Livengood. Below, Marcis at Daytona in the early '70s.

“In those days we had a tremendous problem with cylinder heads cracking,” he continues. “One year, I had some money left over from the points fund and bought five sets of real good heads. By May, most had already cracked.”

Compression ratio was around 13:1, and the biggest valve sizes were 2.050 intake/1.600 exhaust. Depending on the track, Marcis traded between 1.6:1 and 1.65:1 rocker ratios. Total valve lift rarely exceeded .630 inch, compared to the .750 that NASCAR engine builders can achieve today.

Getting around NASCAR rules

“Of course, we had to run a flat-tappet camshaft,” says Marcis. “We used the old Ford-style mushroom lifter to get little more area on the cam. You had to put them in from bottom of the block with the cam out. Then NASCAR outlawed them.”

NASCAR also came down on a Marcis trick when he ran the Hemi engine on restrictor tracks. Dodge commissioned Holley to special build six 4500 carbs for its teams.

“NASCAR mandated a ring that reduced the throttle-bore diameter, and it was pressed into the throttle plate,” explains Marcis. “I had Leo Jackson machine a set of rings in such a way that that there was a real thin cut on the outer edge.”

The new rings fit snugly into the throttle plates and looked legitimate to NASCAR inspectors before the race.

“Then we knocked ‘em out with a screwdriver,” laughs Marcis. “The Hemis had those big box intake manifolds and we put in screens to keep the rings from getting sucked into the ports. In those days you never tore down the engine unless there was a protest. Sometimes [the inspectors] would pull the carb, but they never noticed.”

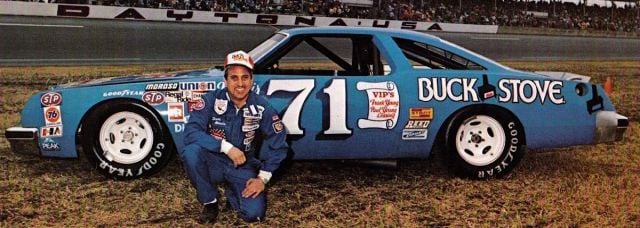

Dave Marcis raced Dodges, Chevys and Buicks throughout his NASCAR career. Below is his standing mile car, which was his last speedway ride. (Photos courtesy of Dave Marcis collection and David Whealon)

“But it didn’t take long for NASCAR to catch on to those tricks,” counters Livengood, adding that playing with weight was more tempting. “We’d stick big, heavy lead bars up the exhaust and wrap a shop rag around the ends before going to the scales. Told the inspectors the rags were to keep dust from going up the pipes. Then we’d pull out the bars before the race. Again, NASCAR caught on quick.”

“But it didn’t take long for NASCAR to catch on to those tricks,” counters Livengood, adding that playing with weight was more tempting. “We’d stick big, heavy lead bars up the exhaust and wrap a shop rag around the ends before going to the scales. Told the inspectors the rags were to keep dust from going up the pipes. Then we’d pull out the bars before the race. Again, NASCAR caught on quick.”

He was just one of those guys who did more with less than anybody out there. — Richard Childress

Among the legal tricks Marcis tried were gas ports on the pistons, reconfiguring the piston crowns for flame travel and exhaust tuning. “We worked real hard on headers to get more bottom end torque, using smaller diameter tubes and making the primaries longer,” says Marcis. “Everybody talks about horsepower, but torque is where it’s at.”

Long before billet crankshafts were available, Marcis took raw GM forgings to Moldex or Hank the Crank for grinding. “Back then we weren’t trying to whittle down the bearing sizes but we were always trying to lighten up components,” says Marcis, adding that dry-sump systems were favored because a wet-sump pan was at the mercy of G-forces in the corners.

“It was just to keep constant oil pressure,” explains Livengood. “It wasn’t until the late ‘80s that we started thinking about pulling pan vacuum.”

“Union 76 supplied oil to every competitor in those days,” adds Marcis. “For a long time we ran straight 50-weight. We didn’t know about lighter oil.”

His most gratifying victory

All of Marcis’ hard work reached a personal zenith in 1982. He had a ’79 Caprice racecar that was whittled down to a 110-inch wheelbase when NASCAR changed the rules.

“I took it over to Richard Childress’ shop because he had a frame fixture to shorten existing cars,” remembers Marcis. “I put on an ’82 Malibu body and made it a short track car.”

Marcis had just one full-time employee, Frank Graham. Following the Daytona 500–in which Marcis led three laps in his Buick speedway car but finished 24th after a piston failure on lap 131–Marcis and Graham dropped a fresh small-block Chevy into the Malibu and headed to the half-mile oval at the Richmond Fairgrounds. Marcis–who hadn’t won in 137 races following his 1976 Talladega victory–qualified sixth for the Richmond 400, moved up to fifth and stayed with the frontrunners until lap 243 when Joe Ruttman put him a lap down. But Ruttman crashed on the next lap, returning Marcis to the lead lap in fourth spot. The leaders–Benny Parsons, Richard Petty and Dale Earnhardt–all dove into pit lane under yellow while Marcis stayed out. Then came a torrential rainstorm, and race was red flagged at lap 250.

“It was a very rewarding race because we were an independent team with my own race car and my own engine,” says Marcis. “I doesn’t get more rewarding than when you do the whole thing yourself. I built my own transmission and rear-end gears. I even drove the tow truck to the race that weekend.”

For the next 10 years, Marcis drove for other owners and didn’t build anymore engines for his cars. Following his retirement in 2002, Marcis opened Street Rods by Dave Marcis in partnership with his son-in-law, Sam Beam, at Asheville (NC) Speed Equipment. The shop features a chassis dyno given to him by Dale Earnhardt and has built a number of tricked-out street machines, including a ’34 Chevy with an SB2 engine.

Still going over 200 mph

Marcis and Livengood are currently collaborating on a standing-mile car. Livengood helped develop the new Chevy R07 engine and was given prototype #003 when he retired from Childress Racing.

Marcis looks over the engine in his standing-mile car. It based on an early Chevy R07 prototype that Dewey Livengood helped engineer for GM racing.

Maxton, North Carolina, was the former site of the standing-mile competition set up by the East Coast Timing Association. Marcis just missed the class record of 205 mph his first time out.

“We went home and worked on the spoilers, air dams and tuned the engine better,” says Marcis, adding that the prototype Chevy V8 puts out 745 horsepower. “Then we went back and set a new record at 216.”

The race site was moved to Ohio this year where Marcis clicked off a 217.619 mph pass. The team is looking forward to a return run and hopefully 220 mph.

It’s the kind of independent, family-style racing Marcis enjoys the most, as evidenced by the zest in his voice when talking about running out of his own shop.

“In those days we only had two racecars, three at the most,” he sums up. “When you brought them home you had to pack the wheel bearings, pound out the dents and get ‘em ready to go again the next weekend. We were short handed all the time. Just had to work our butts off!”