[1]Selecting a camshaft for a given engine’s purpose usually involves a compromise between low- or high-end power options, and the lobe separation angle (LSA) is one of those factors where engine builders have to make a choice between those priorities.

[1]Selecting a camshaft for a given engine’s purpose usually involves a compromise between low- or high-end power options, and the lobe separation angle (LSA) is one of those factors where engine builders have to make a choice between those priorities.

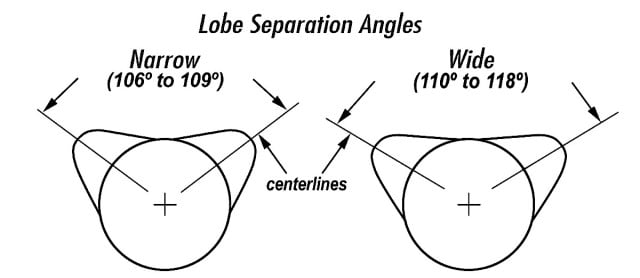

“The lobe separation angle is the angle in camshaft degrees between the maximum lift points, or centerlines, of the intake and exhaust lobes,” says Eric Bolander of Erson Cams [2]. “It affects the amount of valve overlap; that is the brief period of time when both the intake and exhaust valves are open.”

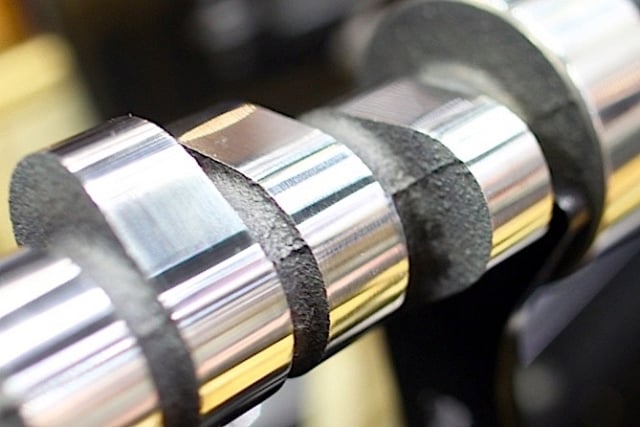

For example, an oval-track small-block that needs to motivate the car off the turns quickly might have a narrow LSA of around 106 degrees, resulting in more overlap. A narrow, more specific power band is also a product of a narrow LSA, as is a lumpy idle quality–often referred to as the 106 sound.

“The tighter the lobe separation angle, the peakier the power curve will be,” confirms Bolander. “It produces peak torque earlier—coming on quicker and stronger—but also it falls off quicker too. On a torque graph it tends to resemble a triangular shape.”

A wide LSA reduces valve overlap, softens the idle and improves overall drivability–especially on the street where performance engines benefit from 112 to 114 LSA. But that doesn’t mean high-strung racing engines can’t see gains, as well.

[4]

[4]A Pro Stock engine builder may prefer a wide LSA to help keep the power from breaking traction tOo early.

“Supercharged and nitrous race engines typically benefit from a wider LSA because they don’t require as much overlap for exhaust scavenging as does the naturally aspirated engine,” continues Bolander. “Also, the wider LSA contributes to chassis stability in drag racing by avoiding the delivery of a ferocious blast of power that would break tire traction. So the wider LSA introduces a broader and therefore longer torque band.”

“Changing the lobe separation angle changes the amount of overlap that exists during the time the intake and exhaust valves are both open,” echoes Doug Patton of Pro Line Race Engines [5]. “On a naturally aspirated engine, the lobe separation angle has an effect on whether the engine reaches peak torque a little earlier or later in the rpm range. Typically, narrower lobe separation develops peak torque at lower rpm and widening the separation tends to build peak torque higher in the rpm range. Nitrous engines, which make plenty of power and torque, often run wide lobe separation angles to moderate cylinder pressures and temperatures.

“Lobe separation angles,” he continues, “are influenced by the camshaft grind. If a street car has smaller lift and duration numbers, they might run 112 or 114. Widening their separation angle helps increase upper rpm power output. Alternatively, if you are running a bigger camshaft to gain maximum top-end power, cam makers often suggest reducing the lobe separation angle to recover power lost in the lower rev range.”

Getting back to the sound of an engine, it’s no secret that a raucous, lumpy idle is often preferred by street cruisers, regardless of the ill manners and inefficiency of such an engine setup. That’s just the way the customer wants to roll, and engine builders find it’s easy to deliver such a powerplant. Chuck Lawrence of Jon Kaase Racing Engines [7] was asked to give a 520ci BBF a “Pro Stock” sound, so he went with a 108 LSA in place of a more conventional 112 LSA.

“The result sounded wonderful, but it didn’t rev as enthusiastically and it made 30 less horsepower than normal,” says Lawrence.

“If you changed the lobe separation of a street engine from 112 degrees to 106 and didn’t do anything else,” adds Kaase. “The engine would idle a lot rougher and generate worse exhaust emissions largely because of unburned fuel.”

One segment that truly benefits from a wider LSA is the marine marine market. Bolander says those cams help promote torque in a controlled and predictable manner, especially in no-wake zones and around the docks. They also reduce stress on the outdrive.

“It’s also critical that valve overlap is kept to a minimum as the induction system can create a suction that pulls water into the motor,” adds Bolander.

Again, these are general bits of conventional wisdom. When boost or nitrous are introduced, and engine builders contemplate choices between single-, dual- or reverse-pattern camshafts — then the discussion gets much more technical.